The Golden Age of Television

It has always amused me that people who attack television as a negative influence and proclaim a desire to give up watching never seem to express the same desire to abandon seeing movies, as though the movie is somehow a higher art form. In the past, such a distinction might have been possible to maintain, but not anymore. Television has experienced a monumental revolution in quality over the past 5-7 years. Of course, I am not suggesting that there no longer exists morally degrading shows on TV. The bad always coexists with the good in any medium. What I am suggesting is that good television has, in the past half decade, gotten immeasurably better.

Part of this is due to the cream of the Hollywood crop (writers, actors, directors) realizing that television allows them creative opportunities that film could never accomplish, such as the ability to develop characters and plot lines over the course of twenty-two episodes rather than having to try and cram them into two hours. Consequently, many of the top artists in their fields now employ television as the canvas on which they now express their art.

So I was intrigued to find confirmation of my theory in the newest issue of Entertainment Weekly. In an article titled "TV is King!" EW's film critic (notice this is written by a FILM critic) argues that what appears on television today is of greater quality than what is appearing in movie theaters. She writes:

Any episode of any Law & Order is better than half the feature-length dramas released each week. Any episode of The Office is better than 80 percent of the comedies. Any episode of The Wire is as good as anything nominated for an Oscar. Television is where interesting indie filmmakers like Michael Almereyda and Darnell Martin go to direct episodic dramas when Hollywood runs out of uses for them, where Crash writer-director Paul Haggis goes after he wins an Oscar, and where great actresses like Jean Smart and Stockard Channing go to dazzle when they age out of Hollywood's camera range. It's where I go every day for cultural grounding, amazed at what point-and-click riches there are to be found while sitting in my sweatpants.

In line with this, here is my list of what I consider the ten best dramas on television right now.

1. 24

Provides more suspense, dramatic tension, and adrenalized action per minute than any film released in the last ten years.

2. Lost

Part mystery, part morality tale, part spiritual meditation, all genius.

3. Battlestar Galactica

This apocalyptic space drama offers intriguing reflections on religion and the quest for meaning and purpose in the universe.

4. Smallville

This show is about much more than simply the birth of a superhero. It is preeminently a show about how fathers shape the lives and destinies of their children. (Jonathan Kent and Lionel Luthor shape their boys in quite different ways.) The very first episode of this show set the tone for its emphasis on moral and character development. Young Clark Kent is walking into the first day of classes at high school when he drops his books. Lana Lang picks one up and says, "I see you are reading Nietzsche. So, what are you, man or superman?" Clark Kent replies, "I haven't decided yet."

5. Veronica Mars

Clever dialogue and great acting combined with intricate mysteries.

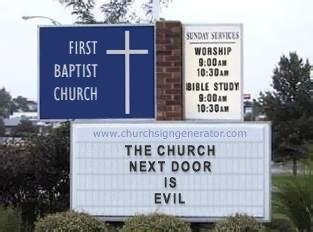

6. Invasion

A roller-coaster ride of a story that also works as an allegory about the strangers among us.

7. Gilmore Girls

To be honest, I have never watched an episode but I do have four seasons of the DVD's to pour through this summer. I include it here because of all the high praise I have heard from others and, especially because if I didn't, I would have to answer to my sister and niece.

8. Supernatural

One of the few televised attempts at horror that genuinely succeeds at being scary.

9. CSI

A show so culturally influential it has spawned articles on the "CSI Effect." Also the favorite of some college president's I know.

10. Everwood

A quality drama with strong characters that regularly addresses moral issues in all their complexity.

One final note: In the same issue of EW, Stephen King writes an article titled "Confessions of a TV Slut," in which he confesses to having ignored TV much of his life until he recently came to recognize the dramatic increase in quality. He lists the six shows to which he is currently most addicted, four of which find a place on my list as well (Veronica Mars, Lost, Battlestar Galactica, 24).